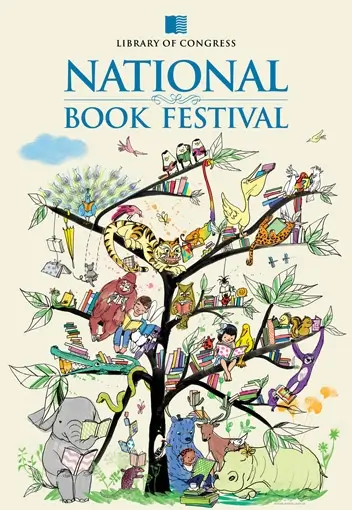

Each year on the third weekend in September, the literary eyes of the nation are focused on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., where thousands of avid readers gather to hear their favorite authors at the National Book Festival sponsored by the Library of Congress. Last year, the Mensa Foundation provided the Children’s Guide to the Festival, and this year the role is expanding to include a Teacher’s Guide and an “Eye Spy” activity connected with the Festival’s poster. The guides will be available here and will be distributed at the festival.

The Foundation’s “contribution to last year’s festival was fantastic and truly appreciated,” said Lola Payne, Chief of Outreach for the festival, who adds that the library is grateful for the Foundation’s expanding assistance with the youth side of the Festival.

The Librarian of Congress, Dr. James Billington, insisted on expressing his appreciation in person for last year’s guide. The guides are written by the Foundation’s Gifted Youth Specialist, Lisa Van Gemert, who says, “It is so gratifying to see young readers walking around the Festival scouring the guides the Foundation provides. Many of these readers are bright, bright kids, and the Foundation’s assistance makes the festival even more meaningful for them.”

Comments (0)