On our 50th Anniversary, we’re proud to celebrate the impact of our awards program, recognizing researchers, academics, educators, and creative individuals who are using their intelligence to benefit humanity.

This year, we’re honored to recognize a pioneer in the field of genetics and intelligence research, educators advocating for equitable practices in gifted education, and researchers whose groundbreaking discoveries advance our understanding of intellectual giftedness. Please join us in celebrating the winners of the Mensa Foundation’s 2021 awards, fellowships, and grants.

Mensa Foundation Prize

As head of the Department of Complex Trait Genetics at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Amsterdam University Medical Centre, Dr. Danielle Posthuma leads a group of 30 researchers from diverse fields, including statistics, stem cell biology, and bioinformatics.

She has led two large-scale genetic discovery studies into intelligence. The first, whose results were published in 2017, led to the discovery of 52 genes linked to intelligence. A year later, in an even larger study of more than 200,000 people, Dr. Posthuma was able to identify another 939 genes associated with intelligence.

“I’ve always been intrigued to know why it’s so easy for some people to learn something, to study, and why it’s much more difficult for other people,” Dr. Posthuma said. “I would really like to understand, what is the underlying mechanism? […] So it’s like with other complex traits; it’s still something that we have to sort out.”

Presented every other year in recognition of a lifetime of contributions to the field of intelligence and related subjects

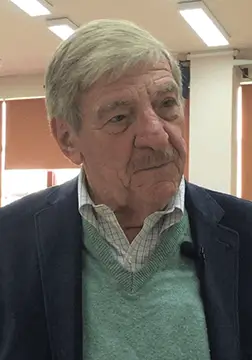

Lifetime Achievement Award

Dr. Joseph S. Renzulli is professor of educational psychology at the University of Connecticut and has served as the director of the National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented and as a consultant to the White House Task Force on Education of the Gifted and Talented.

For more than 40 years, his research and advocacy have reverberated across classrooms nationwide, revolutionizing curriculum development, teaching techniques, and learning models. Dr. Renzulli has been recognized with numerous educational and research accolades, including three Mensa Foundation Awards for Excellence in Research (2003, 2013, and 2019).

“Dr. Renzulli’s lifetime of pioneering research has led to substantial, positive changes in the theory and practice of pedagogy for all,” Mensa Foundation President Charlie Steinhice said. “But what impresses me the most is his dedication to putting those ideas into action, especially for low-income students with high potential.”

Laura Joyner Award

For outstanding work, theoretical or applied, in education, literacy, or work with the gifted or identifying threats to or preventing the loss of intelligence

In its 15-year history, Literacy Now has provided literacy and community-building programs for tens of thousands of Houston-area children and parents, bridging an impasse between public school services and traditionally underserved families.

Founded to address the significant disadvantages children from low-income families face, Literacy Now provides programming that includes small-group reading interventions, afterschool skills-building opportunities, family literacy outreach events, reading readiness classes for parents and toddlers, and more.

“I truly appreciate the opportunity to shine a light on the monumental challenges faced by those struggling with illiteracy and the critical role early intervention plays in eradicating illiteracy and a lifetime of negative outcomes,” Executive Director Jacque Daughtry said.

Distinguished Teacher Award

Recognizing a teacher, professor, or instructor at any educational level who has had an especially positive influence on the education or life of a Mensan

Kristina Tons, an educator for two decades, teaches science to fourth- and fifth-grade students at St. Matthew School in Franklin, Tenn.

In the essay nominating her teacher, Mensan Molly Maguire said she dreaded science but noted how that changed in fourth grade because of Tons. “You can tell every day that this teacher really does love science and loves teaching fourth and fifth graders to love science too,” Molly wrote.

“It is an absolute honor to receive this award and know I have touched the life of one of my students,” Tons said. “It is truly a gift when I see science come to life for my students. It has always been my goal as a teacher to inspire my students by creating fun and meaningful lessons. I hope to instill a lifelong love of learning for the students in my classroom.”

Gifted Education Fellowship (Doctoral)

To assist outstanding educators in acquiring a graduate degree in gifted education or a closely related field from an accredited institution of higher education

As a Teacher Resource Specialist for Gifted and Talented in the West Windsor-Plainsboro (New Jersey) school district and an adjunct professor, Michelle Falanga advocates for equitable practices in gifted education and works with students and their teachers, facilitating programming and providing support.

Falanga received a master’s in educational psychology with a focus in gifted education at the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in gifted education from Rutgers University. She is currently completing her doctoral studies at Rider University, with a focus on the intersectionality of educational professionals trained to work with gifted learners and the execution of appropriate programming to meet their unique cognitive and affective needs.

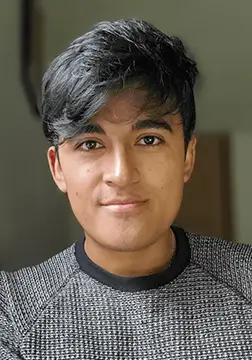

Gifted Education Fellowship (Doctoral)

To assist outstanding educators in acquiring a graduate degree in gifted education or a closely related field from an accredited institution of higher education

Fabio Andres Parra-Martinez is a Colombian doctoral candidate in gifted, creative, and talented studies at Purdue University.

He completed his undergraduate thesis at the Gifted Education Research and Resource Institute (GERI) at Purdue — an experience, he said, that “opened my eyes to the value of gifted education to enhance the progress of people and society” and that led to him joining the doctoral program.

“My research resonates with Mensa’s mission of identifying and supporting gifted youth around the globe,” Parra-Martinez said.

Gifted Education Fellowship (Non-doctoral)

To assist outstanding educators in acquiring a graduate degree in gifted education or a closely related field from an accredited institution of higher education

Katie Lee, a Washington STEM educator, passionate advocate, and community builder, was recognized by the Mensa Foundation to support her in her pursuit of a master’s in gifted education from Johns Hopkins University.

She holds bachelor’s degrees in science (actuarial math) and education, and she is an active member of the National Association for Gifted Children, the Northwest Gifted Child Association, and the Washington Association of Educators of the Talented and Gifted.

“I hope to continuously grow in the gifted education field, and I believe the Mensa Foundation Fellowship will accelerate this journey,” Lee said. “I plan to learn from the most recent research and experts in gifted education through my graduate study and apply these learnings in my community.”

Awards for Excellence in Research

Given internationally for outstanding research on intelligence, intellectual giftedness, and related fields

The outstanding research recognized in 2021 includes a historical review of the oldest and longest-running longitudinal study in the field of psychology, a review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of educational intervention efforts, a comparison between high- and low-income students of the perceived barriers to education, and latent profile analysis to develop psychological support programs for honors college students.

Congratulations to the following researchers:

Senior Division

Dr. Jennifer Riedl Cross, College of William & Mary: “Psychological Heterogeneity Among Honors College Students,” (coauthors Tracy L. Cross, Sakhavat Mammadov, Thomas J. Ward, Kristie Speirs Neumeister, and Lori Andersen)

Dr. Tracy L. Cross, College of William & Mary: “A Comparison of Perceptions of Barriers to Academic Success Among High-Ability Students from High- and Low-Income Groups: Exposing Poverty of a Different Kind,” (coauthors Jennifer Riedl Cross, Andrea Dawn Frazier, and Mihyeon Kim)

David Lubinski, Vanderbilt University: “Intellectual Precocity: What Have We Learned Since Terman?” (coauthor Camilla P. Benbow)

Kate Snyder, Hanover College: “Interventions for Academically Underachieving Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” (coauthors Carlton J. Fong, Jackson Kai Painter, Caroline M. Pittard, Sebastian M. Barr, and Erika A. Patall)

Junior Division

Lisa Bardach, University of York: “Smart Teachers, Successful Students? A Systematic Review of the Literature on Teachers’ Cognitive Abilities and Teacher Effectiveness,” (coauthor Robert M. Klassen)

Brian Bernstein, Vanderbilt University: “Psychological Constellations Assessed at Age 13 Predict Distinct Forms of Eminence 35 Years Later,’ (coauthors David Lubinski and Camilla P. Benbow)

Darya L. Zabelina, University of Arkansas: “Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions in Creativity,’ (coauthors Naomi P. Friedman and Jessica Andrews-Hanna)

Comments (0)